German Christmas Decorations from the Erzgebirge

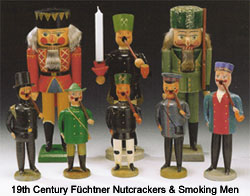

About the Christmas Folk Art of the ErzgebirgeIn the decorative Christmas art of Seiffen we see both the culmination of the woodworker's craft and a reflection of the region's heritage. The variety seems almost infinite: Here may be found simple ornaments and baroque pyramids, biblical tableaux and scenes from the mining life, angels and chimneysweeps. One should not underestimate the value placed on light by the Erzgebirge community of miners. The miners depended on artificial illumination for their work under ground, and they longed for the natural light of the surface. It is no wonder, then, that although the last tin mine in Seiffen closed in 1849, light remains the central theme of that town's folk art, especially at Christmas time. One should not underestimate the value placed on light by the Erzgebirge community of miners. The miners depended on artificial illumination for their work under ground, and they longed for the natural light of the surface. It is no wonder, then, that although the last tin mine in Seiffen closed in 1849, light remains the central theme of that town's folk art, especially at Christmas time.Wooden Angels and MinersNowhere is this theme more apparent than in the recurring figures of the Erzgebirge Bergmann or miner, and the Angel of Light. He is the older symbol, his origins traceable to pieces used in the Erzgebirge churches of the 17th century. The Angel of Light—with her hat which echoes the miner's—most likely originated around 1830, during the Biedermeier period when angels were a popular ornament. She almost always is found paired with the miner.Both were first introduced as simple, skittle-shaped figures, candlesticks whose forms echoed those of lights used in the mines. They have since evolved into one of the most common symbols in the folk art of the region. The pair are now to be found in a great variety of sizes and styles, from the most naive to the most elaborate, both as freestanding figures and as decoration on such items as pyramids and schwibbogen. Christmas Candle Pyramids While market demands largely determined which wooden toys a Seiffen craftsman might produce, the Christmas folk art frequently was shaped to meet the maker's own needs. The Christmas pyramid, for instance, originated as a decorative source of illumination for the toymaker's own home, and as such was influenced not by outside forces but by his own fancy. With such a piece the craftsman could experiment and even show off his abilities as a designer and woodworker. These candle pyramids were not available commercially until the first years of the 20th century, although they had been produced already for half a century or more. While market demands largely determined which wooden toys a Seiffen craftsman might produce, the Christmas folk art frequently was shaped to meet the maker's own needs. The Christmas pyramid, for instance, originated as a decorative source of illumination for the toymaker's own home, and as such was influenced not by outside forces but by his own fancy. With such a piece the craftsman could experiment and even show off his abilities as a designer and woodworker. These candle pyramids were not available commercially until the first years of the 20th century, although they had been produced already for half a century or more.By the 1850s the Seiffen Christmas pyramid had assumed a fairly standard form, of graduated tiers alternately presenting biblical scenes and depictions of the rural or mining life. Perhaps because it was originally a very personal work, its mechanism, its design and its subject matter all reflect the heritage of the craftsman. The candle pyramid's revolving parts are most likely derived from the whims used to draw ore up from the mines. The straight lines of the hexagonal case highlight through contrast the figures, which are turned on a lathe after the Seiffen fashion. The combination of secular and sacred motifs reflects regional pride as much as religious sentiment. Schwibbogen and Candle ArchesOn Christmas Eve, during their Christmas service, the Erzgebirge miners would hang lighted lamps around the arched entrance to the mine. This ceremony was presumably the inspiration for the Schwibbogen, the candle arch thought to have been first made by Johann Teller in 1726. His was of wrought iron, as were most of the schwibbogen made over the next two hundred years. It was not until after 1930 that the Seiffen woodworkers produced their own candleholders in this form. They remain one of the folk pieces most closely identified with the Erzgebirge, and at Christmas may be seen adding a festive glow to the towns and villages of that region.Nutcrackers and Smoking Men There is perhaps no secular figure more closely associated with Christmas than the Nutcracker King. Immortalized in story, music and dance, the nutcracker is an object known worldwide. But while such carved, levered figures have been known for centuries, it was not until around 1870 (some fifty years after Hoffmann's "The Nutcracker and the Mouse King" was written) that the first nutcracker in its now-familiar form was carved by Wilhelm Füchtner (1844-1923) in his Seiffen workshop. There is perhaps no secular figure more closely associated with Christmas than the Nutcracker King. Immortalized in story, music and dance, the nutcracker is an object known worldwide. But while such carved, levered figures have been known for centuries, it was not until around 1870 (some fifty years after Hoffmann's "The Nutcracker and the Mouse King" was written) that the first nutcracker in its now-familiar form was carved by Wilhelm Füchtner (1844-1923) in his Seiffen workshop.In his work as a toymaker, Wilhelm carried on a generations-long family tradition. His ancestors were carpenters who turned to woodcarving in the wintertime to provide for their families. Gotthelf Friedrich Füchtner is recorded as having sold figurines at the Dresdener Striezel Market in 1786. Today, this legacy is continued by Volker Füchtner, the great-great-grandson of Wilhelm and the sixth generation to run the family workshop in Seiffen.  From the beginning, the nutcracker carvers used their work to satirize authority figures—kings, soldiers, foresters, and the like. Smoking men, on the other hand, gently poke fun at the man on the street—the chimney sweep, the postman, the peddler, and even the miner. Where the former appear grim-visaged and stern, the latter seem jovial and easygoing, taking time to enjoy their pipes. From the beginning, the nutcracker carvers used their work to satirize authority figures—kings, soldiers, foresters, and the like. Smoking men, on the other hand, gently poke fun at the man on the street—the chimney sweep, the postman, the peddler, and even the miner. Where the former appear grim-visaged and stern, the latter seem jovial and easygoing, taking time to enjoy their pipes.By the early 19th century, pipe-smoking had caught on throughout Europe, and it quickly took the fancy of the toymakers. Smoking men (or smokers) were being produced in Germany as early as 1800, as patternbooks from that period show. The basic form has remained largely unchanged over the years: the lathe-turned, hollow body holds an incense cone which, as it slowly burns, releases smoke through the figure's mouth. Today the variations on this design are myriad, ranging from the traditional to the contemporary. Further InformationWe urge you to visit the site of the Spielzeug Museum in Seiffen, where you will find further information regarding the traditions of craftsmanship in the Erzgebirge. Although much of the site is in German, there is an informative overview of the region's heritage in English, as well as wonderful pictures of Erzgebirge folk art through the years. |

Contact Us The Wooden Wagon 89 Elm St New Salem, MA 01355 Customer Service info@thewoodenwagon.com Orders orders@thewoodenwagon.com Returns returns@thewoodenwagon.com Links About Our Toys About Our Folk Art About Our Christmas Folk Art Impressions (weblog) |

Don't Miss Anything!

Join our mailing list to learn about news and updates and receive $10 off your next order.